Looking Beyond the Behaviours

Standards and Regulations

The Fostering Services (England) Regulations 2011:

- Regulation 11 - Independent fostering agencies—duty to secure welfare.

- Regulation 13 - Behaviour management and children missing from foster parent's home.

- Regulation 17 - Support, training and information for foster parents.

Fostering Services National Minimum Standards (England) 2011:

Related guidance

All children placed with foster carers will have experienced some degree of developmental and relational trauma (including in utero) so will need empathic, curious, and healing parenting from their foster carers. Clear boundaries, expectations and routine are also really important as they create a sense of safety and predictability and over time this also helps to build trust.

Fostering involves looking beyond the behaviour and being curious about what lies behind it. Seeing behaviour as communication and trying to understand it in the context of the child’s experiences will help you to think about how best to manage the behaviour and how to notice and talk to the child about it. For example, recognising that a child is always distressed at bedtime may prompt you to acknowledge with the child that bedtime might have previously been a difficult time for them, and you can collaboratively think about how the routine can be adjusted or what can be put in place to help the child feel safer. If behaviour is only addressed in the moment, the likelihood of future change is smaller. Being curious is therefore central to therapeutic parenting.

When a child arrives in your home, they will likely be scared and unsure of what to expect. Their internal working model is likely to be one in which they view themselves as bad, experience has taught them that adults can’t be trusted, and the world feels unsafe. As such, they will likely be afraid of you as a caregiving figure and many children’s way of trying to manage this themselves is to control. As such, it is important that the house rules are established very early on, and that the child can be supported to understand these rules in the context of their ability. It is helpful to revisit these rules again when the child is a little more settled as they will likely find it difficult to take them in when they first move due to the trauma of moving. Don’t forget to re-visit your Safe Care Family Agreement with the support of your Supervising Social Worker as well in the context of any information you have about the child you are fostering.

It is important to note that all children are different. Some children will appear to settle very quickly, and then more distressed behaviour will emerge as they feel safe enough to display this. Other children will display their hurt more overtly through their behaviour from the start of them living with you. They may be difficult to engage, or they may be triggered very easily and respond reactively. Carers have access to training about attachment, trauma and brain development, which is covered within the mandatory programme, to support with understanding these behaviours in the context of their earlier experiences but they are briefly covered here.

When you are setting boundaries for children, for example whether or not they can go to a party, you need to think about the child’s developmental and experiential age, not just their chronological one.

- Chronological age – the actual number of years they have been alive;

- Developmental age – The age the child is functioning at developmentally in terms of what they can/ can’t do. Trauma has an impact on development because the brain is focused on survival over learning. A child may also have been neglected so may not have had the opportunity to learn skills in line with their peers. Some children may also have a learning difficulty or disability that means that they function at a younger age developmentally;

- Experiential age – Children who’ve experienced trauma have been exposed to things that even children chronologically older wouldn’t have experienced. For example, caring for a younger sibling from as young as 3, or cooking their own food from a young age, or caring for an intoxicated parent. This means they may well be older than their chronological age in some ways or have knowledge outside of the sphere of their peers. Equally their experience of play opportunities may have been limited and impacted on their experiential age.

Your relationship with the child you are fostering is hugely important in supporting the child throughout their lives. As Dr. Bruce Perry states, “Children are wounded in the context of interpersonal relationships. Children can only be healed in the context of healthy, nurturing interpersonal relationships.” Caregiver-child interactions have the potential to shape the thinking and feeling and ultimately the behaviour of the child. Therefore, building a positive relationship with the child is central to your fostering role.

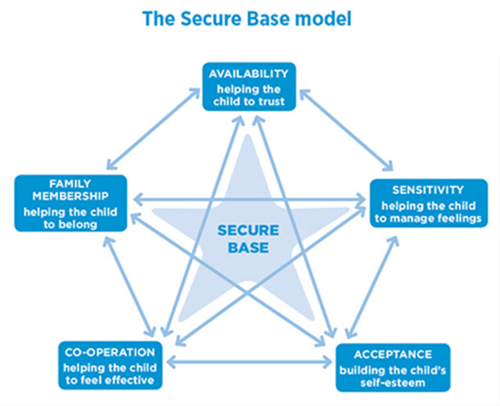

The Secure Base Model can help you to think about the primary areas of focus for a child to form a positive relationship with you as their caregiver and to feel safe enough to explore and learn while trusting that you will remain there for them when you can’t see them. This is something every child needs to feel but children who’ve experienced trauma will not feel this when they are initially placed, and it will take varying degrees of time to develop.

The caregiving dimensions can be seen in capitals.

These are the things that you can offer a child to support them in developing a safe base with you. The lower-case text (trix can we make this bold) shows the corresponding developmental benefit that a child gets when you are offering this to them. All of your interactions with a child, however menial, have an impact on the way the child thinks about themselves, others and the world. The star shows the interplay between each caregiving dimension.

You can see more information about the Secure Base Model on the UEA website.

Children need to have clear boundaries and will need their behaviour challenged and understood. As mentioned previously, this helps children to feel safe. However, it is important that as foster carers and the team around the child, you are thinking about the particular needs of the child or young person you are fostering and thinking outside the box to more therapeutic ways of parenting.

Why doesn’t traditional parenting work for children who’ve experienced trauma?:

- They haven’t experienced consistent connection;

- They are often afraid of adults due to their experiences;

- Oftentimes they can’t control their behaviour/inhibit impulses;

- Traditional parenting relies on a healthy attachment between child and parent, with trust and safety securely intact;

- Children learn about consequences from the arousal-relaxation cycle early on in life. Without this foundation, understanding of cause and effect is distorted and they can’t regulate;

- They haven’t experienced unconditional love and see themselves as bad;

- They experience shame (I am bad) rather than guilt (I did something bad).

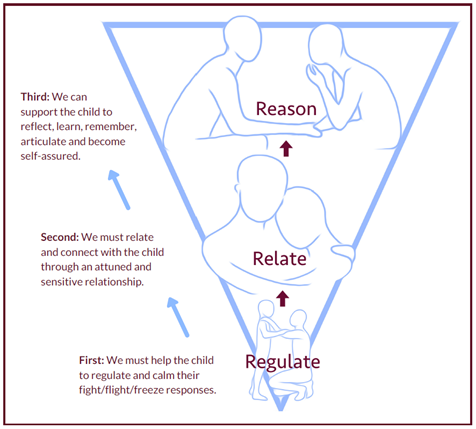

We know from neuroscience and brain functioning that children need to be regulated before they can take on reason, logic or learning. It can be helpful to follow Bruce Perry’s 3 R’s (to be read from the bottom up) – Regulate, Relate, then Reason.

Regulation techniques such as mindful breathing, yoga, and movement are explored within the mandatory training. You will need to find what works for the child you are caring for and ask their Social Worker what has helped before (if known). Regulation helps to bring a child back to calm so that they can access the parts of the brain capable of complex thought and reasoning.

Changing the environment, such as going to the park for space to run around, before the situation gets to boiling point can also work well.

Once the child is regulated, start with empathy for the way the child is feeling. This replicates the arousal-relaxation cycle for babies and young children which will not have been completed satisfactorily enough times while in a traumatic home environment.

Try to identify what the anger is really about and how can you reduce their stress. It can be really difficult to stay calm but active and empathic listening to a child can support co-regulation. Accept what is happening, that you can only control your responses, and try to focus on your own breathing. Think about your non-verbal communication; your gestures, facial expressions, body language, as well as the tone and volume of your voice.

In certain circumstances, (where the child’s safety or the safety of another child or person may be in question if the child leaves the room or premises), good practice involves communication to try and persuade the child on a different course of action. However, where this is ineffective, the carer should reinforce dialogue with such actions as standing in the way of a child wishing to leave, or may place a hand on the child’s arm, or hold the child if they are highly distressed or in danger, for example if a child is trying to run out of the house onto the road in a distressed state. These methods should only be used for the minimum time needed and with the minimum force necessary to ensure the child’s safety. The child should always be told that the Police will be involved if they run away. Any sanctions or interventions used must be recorded straight away in the child’s daily diary.

These approaches are used in the context of engaging the child/young person in discussion about their behaviour, listening to them and showing empathy to their distress.

For children who become violent or aggressive, de-escalation techniques can support in not picking up the metaphorical tug of war rope and parking the conversation until a child is regulated. Your response, body language and communication of empathy will support a situation to calm in the moment (see also Restrictive Physical Intervention and Restraint).

Exploratory conversations when everyone is calm are opportunities to listen to a child’s point of view and to support them in their self-understanding in a non-shaming way. These need to happen at a time when the child is able to take it on board rather than tackling big issues head on in the moment.

Structure and routine is really important for all child but especially those that have experienced unpredictability in their past. Building in time in the routine for physical activity, down time and connection time with you as their foster carer will be a huge preventative factor to situations escalating.

Identifying triggers for repeated behaviours can be helpful too as there may be things you can proactively change or talk to the child about beforehand.

Changing the environment, such as going to the park for space to run around, before the situation gets intolerable can work well.

Explaining to children how their brains work and why they may find certain things difficult in a non-shaming way can also be helpful. The Empowerment Approach offers a child-friendly language to support you in doing this.

Looking behind the behaviour requires a bit of detective work on the part of the foster carers and Social Workers around the child. It is important that everyone is working together to be curious about the child using knowledge about their individual experiences and about the areas below:

- Attachment – The relationship between someone who is vulnerable and dependent, in this case a child, and someone who is not. In optimum conditions, it is a care-seeking/caregiving relationship. Attachment is a behavioural strategy utilised at times of actual or perceived stress/threat/danger to maximise safety and comfort, so we all display attachment behaviours. Some children have maximised their safety and comfort by (unconsciously) supressing their own needs and feelings and being quite self-reliant. Others have found the most effective way to get their needs met in their family was to (unconsciously) shout the loudest or to exert their own control. Children will carry attachment behaviours with them into foster care and while they may have been effective in the context of their family when they were experiencing abuse or neglect, they may well be ‘maladaptive’ in your home i.e. no longer effective. But it will take time, trust, and evidence that other behaviours are more effective before they can let go of these and even then, they will likely revert to these childhood attachment behaviours when under stress, just as we do. An awareness of your own attachment behaviours can really help you to understand your responses to children’s behaviours too;

- Developmental Trauma – Developmental trauma refers specifically to trauma in childhood which interrupts their development. A huge amount of brain development takes place after birth including a child’s internal working model (view of themselves, others and the world), how relationships are built (attachment), cause and effect, and emotional regulation. Trauma often comes out in our bodies somatically, for example with stomach aches, and/or in our behaviour and the way we relate to others;

- Brain development – The brain develops sequentially from the bottom up with a huge amount of human brain growth post birth to allow us to adapt to our environment. A really good resource to understand this further can be found on the Beacon House website;

- Shield of Shame – Children who’ve experienced trauma often feel a deep sense of shame, feeling that they are bad and unworthy of love and care which can be a very painful thing to think about oneself. As a result, the brain employs other strategies to protect them from this which is sometimes referred to as the shield of shame. This includes behaviours such as lying, blaming, minimising, rage or bravado. This can be an additional mask to their attachment behaviours.

- PACE - Playfulness sometimes defuses a situation through being silly. Accept the child in their entirety, which doesn’t mean you accept their behaviour e.g. I know you can put this right because I know you have a good heart. Curiosity about what lies behind the behaviour. Empathy for the child, putting yourself in their shoes which can be really hard to do at times. Deal with your emotions afterwards, you’ll need to have your own strategies to do this. A useful PACE video to watch is this one from DDP;

- Routine, structure, boundaries - Keep very regular mealtimes, bedtimes etc. Be clear with your language;

- Consistency, predictability, reliability - no surprises as surprise equal fear;

- Be the unassailable safe base – as discussed above;

- Non shaming – Remember that children who’ve experienced trauma often can’t feel guilt, only shame;

- Empathic commentary/Name it to Tame it - Never ask why they did something. Instead give them 'time in' e.g. I can see you’re struggling with this, I think you need to stay close to me so I can make sure you’re safe;

- Naming the need/the gift of why - help them to make sense of their own behaviour e.g. I’ve noticed when x happens you do y and I’m wondering if this might be about z;

- Connection at all times – think about how you maintain a psychological connection when you’re physically apart. For example, when a child is at school you might give them a note in their lunch box or something in their pocket to look after;

- Natural and logical consequences - e.g. if they spend all their money, they haven’t got any money;

- Regular relationship repair – Nobody can be therapeutic all the time but admitting when you’ve not been and repairing teaches them valuable lessons about relationships.

If the child is moving on to another carer or is returning home, be sure to share the knowledge you have learned about the child, including your understanding of their behaviour and things that have or haven’t worked. Activities that support that individual child to regulate can be particularly helpful. Sharing your knowledge will be beneficial to the child’s next primary carers/parents and will support consistency through ongoing conversations with the child.

There are lots of recommended resources to learn more about this within the Local Resources and within the foster carer training programme.

Please also seek support and opinion from the team around the child and raise any concerns.

Last Updated: September 30, 2024

v29